Digital Commentary Driving: a missed opportunity for UK leadership in automated vehicle safety assurance?

2026 will mark five years since BSI (British Standards Institution) published the report led by myself and PKS Insights in which we set out the concept of Digital Commentary Driving (DCD). This we proposed as a standardised approach to capturing, structuring and sharing automated vehicle (AV) data to support safety assurance, regulatory oversight and public trust. This was developed because BSI had identified that a standardised approach to automated driving safety assessment was the most significant gap in the AV standards landscape.

At the time, the UK was well placed to take this idea forward with an active AV trial ecosystem, a pragmatic regulator and a clear ambition to be a world leader in the safe deployment of automated mobility. Five years on and despite enthusiasm from regulators, DCD still remains largely conceptual. We have missed the opportunity to gain five years of experience in collecting DCD data from AVs and developing the thresholds that represent acceptable and unacceptable driving behaviours - and the tools to perform such analyses. However, despite there being little in the way of better ideas to achieve the aims of DCD and frustrations from stakeholders about how safety assurance will be achieved, we have to date missed the opportunity for the UK to shape the global conversation on how AV safety is demonstrated and communicated.

The core insight behind DCD is straightforward. Commentary driving for humans is where the driver verbally articulates hazards, intentions and decisions to demonstrate competence. Digital commentary driving is intended to capture the same information but in a continuous and standardised data stream. The intention is that analysis of this data would enable regulators to confirm that an AV has all the information necessary to drive in a careful and competent manner (as required by the AV Act 2024) and that it makes appropriate decisions about its future speed and path based on that information.

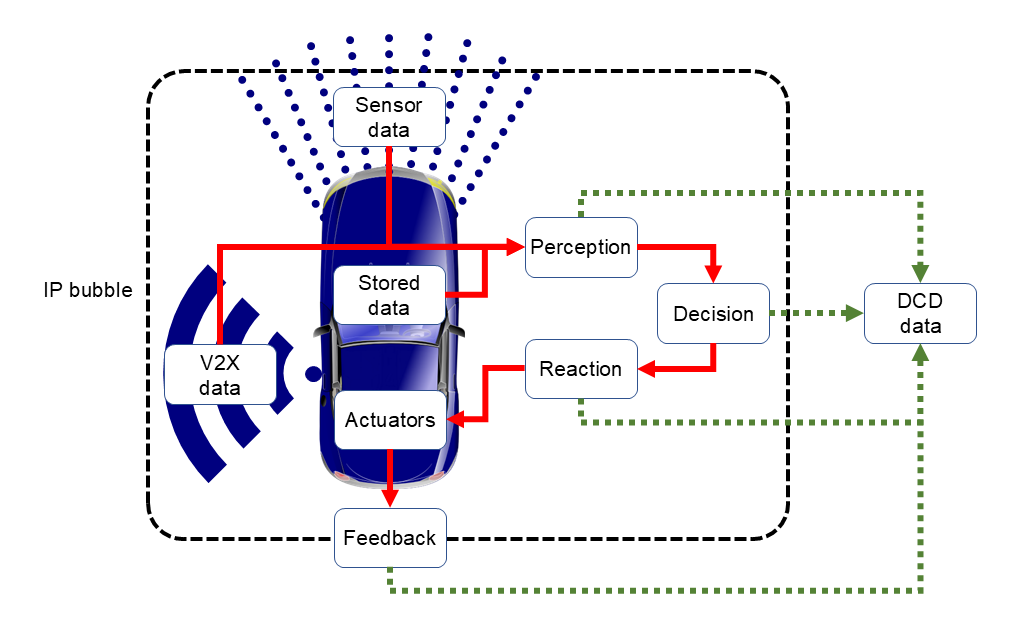

Figure 1. Conceptual overview of how Digital Commentary Driving Data would be collected

The need for DCD was highlighted at CES 2026, with Nvidia announcing its intent to develop self-driving vehicles using ‘Alpamayo’, which it describes as ‘…a family of open-source AI models and tools to accelerate safe, reasoning-based autonomous vehicle development’ and making the claim that their approach will ‘enable the development of vehicles that perceive, reason and act with humanlike judgment’.

Will it though?

My fear is that this will apply LLM text production to AI-based automated driving behaviours that essentially offer a (albeit highly persuasive) post-hoc rationalisation of how the vehicle is choosing to behave. This will be tremendously powerful for building public trust but will not get at the essence of how the AV is operating. To do so necessitates access to the data that the AV is using to inform its actions.

DCD’s role is therefore particularly important in the context of trust. It is reasonable to assume that human drivers usually operate with:

a sense of self-preservation;

a desire not to harm others or cause damage to property;

to follow the rules of the Highway Code (and recognise that there are consequences for non-compliance if caught).

By contrast, we cannot make the same assumptions about the behaviours of AVs. The aim of DCD is to offer a bridge between opaque automation and the legitimate needs of regulators, safety assessors, investigators and the public. This is achieved by requiring AV operators to produce a structured, machine-readable dataset from the operation of their vehicles that provides the substrate for independent analysis of what the vehicle perceived, what it assessed as relevant risk, and why it acted as it did.

DCD is not intended to be a real-time explanation system for occupants nor as a substitute for rigorous safety engineering. It is intended as a regulatory safety assurance tool for in-use monitoring: a way to evidence that an AV is operating within its defined Operational Design Domain, complying with traffic rules, responding appropriately to hazards, and degrading safely when limits were reached. Standardisation is a key enabler. Without common data structures, taxonomies and performance indicators, safety assurance risks fragmenting into bespoke, non-comparable claims across AV developers and ODDs.

Similarly, the DCD approach requires data that AVs must be using to drive safely. For example, an AV driving through an urban environment must demonstrate that it is identifying the presence of other vehicles, pedestrians and other objects and making suitable predictions about their future movement. However, DCD does not care how that data is derived - whether using cameras, radar, lidar, ultrasound or thermal imaging - or whether using a fixed rules-based approach or end-to-end deep learning. Consequently, it can exist outside of what we described as an ‘IP bubble’ (see Figure 1), without compromising commercially sensitive data.

Since 2021, the UK’s AV safety discourse has focused on legislative frameworks, high-level safety principles and company-specific safety cases. These are of course necessary but are not sufficient. The AV Act sets the safety ambition but it does not solve the practical problem of how safety is evidenced consistently across developers, deployments and time. In the absence of a standardised approach like DCD, regulators face an asymmetry of information where the public is essentially asked to trust systems whose actions cannot be meaningfully understood.

Other jurisdictions and international bodies are now grappling with similar challenges around explainability, post-crash data access, and ongoing safety monitoring. The UK could have been setting the agenda by developing DCD into a recognised national and international standard, piloted through trials, embedded into assurance processes, and aligned with UNECE, ISO and EU initiatives. Instead, the window for clear first-mover advantage has narrowed.

That window of opportunity is still open. Excitingly, I am helping to supervise a PhD on the use of DCD for AV safety assurance at the University of Surrey, which will kick off this year. However, as AV deployments move from trials to scaled services, the need for transparent, auditable and comprehensible safety evidence will only become more urgent. Revisiting DCD, not as a theoretical construct but as a practical standard co-developed by industry, regulators and the safety community, could still help the UK demonstrate global leadership. More importantly, it could help answer the question that ultimately matters most: not just whether automated vehicles are safe but how we know they are.